Meet the Author: Megan Westley – Living on the Home Front

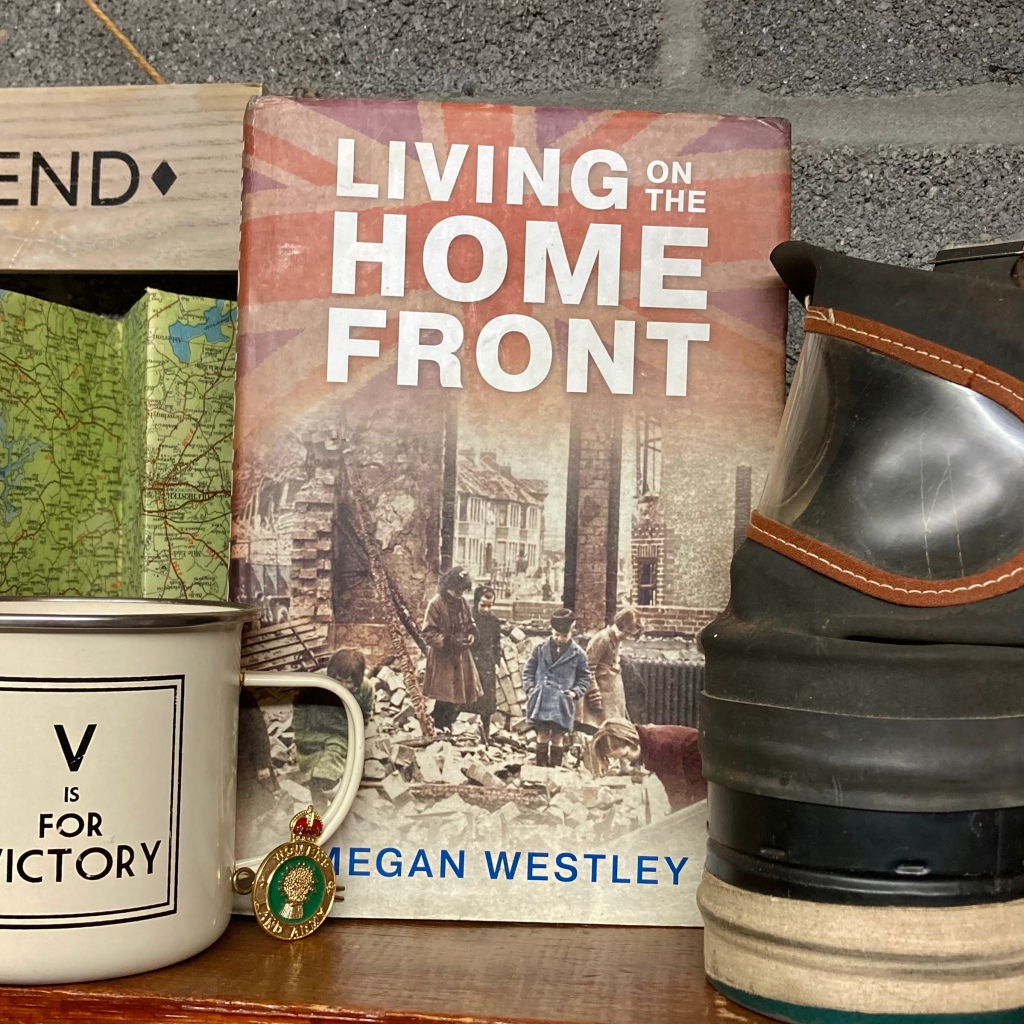

I have a little pile of books in my life which I can read again and again and an even smaller pile that inspire me as soon as I read them, Living on the Home Front by Megan Westley is one of those magical books that fits into both these categories.

Written in part as factual chapters full of Home Front information and part in diary form with recipes dotted inbetween, Megan decided to live a year on the Home Front, rationing and all, as part of her passion for the era and a curiosity to see if living 1940’s style would be able to solve some of the problems of today.

As you can imagine, I was very enamored the concept of this book. My Home Front Solutions are all about testing the idea that bring backs Home Front ideas would make our lives greener, happier and healthier but I’ve never been brave enough to go the whole hog (I love pink hair dye and pinterest a little too much) so this book answered so many questions I had but also gave me a lot more.

So last year I approached Megan on Instagram to see if she would be happy to answer some of my questions that the book through up and for me to share with on here and happily she agreed.

I hope you find this as fascinating as I did, it was brilliant to hear some of the background to the experiment and how many parts of it are still present in her life (though maybe not the corned beef). I also found it really interesting how she linked her Home Front experience to the cost of living crisis now and her feeling on our attachment to our phones and producitivity, I’d love to know what you think so please comment below.

Beginning

To have undertaken such a project, you must have a real passion for WW2 and the Home Front. When did your love of the era start and was in anything in particular that set it off?

It all started back in childhood – I’ve always been absolutely fascinated by history, especially the details of domestic life. Here in Cornwall, there’s a theme park called Flambards, which has the Victorian Village and Britain in the Blitz exhibitions. You can walk around and peep through the windows of display shops and houses, and to the childhood me it was the Best. Place. Ever. I requested to go there every year for my birthday, and would spend ages wandering around these little time machines, soaking in the details. It planted a seed of interest that’s been growing ever since.

Even though I’m someone who is intrigued by Home Front history and trying to bring a little bit of it into my modern life, I’m not sure I could have done it for a year, what was your motivation to carry out the experiment and for the length of time?

I did consider carrying the experiment out over a shorter period of time, but I felt that a degree of ‘suffering’ was important to making it more accurate! Doing a whole year also meant that I was able to encounter all the seasons, which actually ended up being one of the most interesting parts of it. Growing your own food, buying fresh and local, and even spending your time without television: they’re all affected massively by the seasons. In the summer, I was really busy in the garden, out walking in the evenings, and preserving things… In the winter, it was far more about tidying up, planning, and staying in. Obviously, we’re all aware of the changing seasons, but things like television and supermarkets do flatten the seasonal differences.

You were living with your sister when you took part in this and knowing what my sister would have said, I’m wondering how did she and also your partner react to this idea when you first suggested it and how easy they found it to support the project as the year went on?

My then-partner Benjamin, who’s now my husband, is brilliant in this regard – he’s always the person saying ‘yes, go for it! Of course you can do that!’ When we were together during that year, he never grumbled about eating differently, not watching television, being put to work, or any of it. He threw himself into the whole thing with me 100%. That’s the kind of person you want on your side for life. As I was living with my sister, I think she was probably more naturally concerned about it being disruptive. However, we were both adults and so were living our own lives too; we often cooked separately anyway, and had our own hobbies, so didn’t live in each other’s pockets. I had to take myself upstairs in the evenings when she wanted to watch television, and I do remember there being one night very early on, when we both went to my mum’s for what was traditionally a Chinese takeaway and television night. We had a bit of a tussle over the food and viewing situation, and in the end, the wartime experiment won out, but it did get a bit tense for a moment! Having said that, she was very tolerant in other ways; not least when my homemade wine exploded right next to her during a particularly enthusiastic fermentation period. I heard a bang, closely followed by a scream, and knew exactly what must have happened

Having the chapters split by a general run down of each year and more in-depth description of certain parts of the Home Front before you got to your diary entry was really interesting, did you allow internet searches for this and your recipes or was it all

old fashioned book searching?

I used a lot of historic books and printed materials when I was researching – things like wartime cookery books, Dig for Victory guides, collected Make Do and Mend pamphlets, and even the German invasion plans for the British Isles. I did allow myself to use the internet to access archival sources that I needed; things like historic newspapers from the time (via the British Library’s newspaper database). I tried not to rely on second-hand information that was out there, because it’s so easy for one person to make a mistake on a date, or misinterpretsomething, and suddenly you see it repeated in ten other online articles. For the specific details of when rationing changed, or new Government measures were announced, I trawled through reams and reams of old newspapers. This is actually something that I love though – I can lose hours of my life once I get on the scent of an interesting story.

Did you find much out about your own local and family WW2 history through the project?

I was very lucky to have my grandmother around at the time of this experiment, so I was able to ask her a lot of questions. She was a teenager during the war, and worked in a local grocery store, so she was responsible for weighing out rations, taking the coupons, and so on. She was an extremely bright and sharp lady, so she remembered all of it and could share her stories. My granddad and his family were farmers, so on his side, he worked with Italian prisoners of war, and remembered things like the Women’s Land Army being around.

I really love the fact you included recipes and I’ve tried nearly all of them with varying success, what was your favourite wartime meal and which one was your most hated?(Can I guess it involved the infamous powdered egg?)

Surprisingly, it didn’t! I think one of the worst things I had to eat was a wartime recipe for corned beef with haricot beans. This was at the point where the meat ration was pretty low, and a mandatory part of it was corned beef. I’m not the biggest fan of corned beef at the best of times, but this particular dish made it wet and sloppy. I made it a point of principle to finish what was on my plate at every wartime meal, as I didn’t want to waste food. Some of it was bland and boring, but I always managed to finish it. But with this corned beef dish, I almost reached my limit. I tried giving the last of the gravy to my cat (who was famously greedy and would eat literally anything). He wouldn’t touch it. After that, I often chose to forego the corned beef ration and just have less meat as it had put me off it.

What was the modern food you missed the most as the year went on?

To begin with, I missed the things that you’d probably expect: modern convenience food, crisps, and so on. But as time went by, the foods that I missed the most tended to be out of season fruit and veg. When you’re eating completely seasonally, winter can be quite boring. I remember seeing the first local broccoli of the year and feeling so excited. One of the first purchases I made was two bananas – such a simple thing, but wonderful after not being able to have them. This recollection makes me smile now, because it’s clear how much the wartime mindset had got to me by then: I could have splashed out and bought a whole bunch of bananas, but instead I only chose to buy two, because they seemed so rare and exotic, and I wanted to savour them.

On the broader theme of missing out, what did you miss most about modern life in general and were there any parts of modern society you could live without once the experiment had finished?

It sounds crazy to me now, but having to give up television was one of the things that initially

made me second-guess carrying out the experiment; I was worried that I wouldn’t be able to last the year without it. That was a transition that I had to go through (though I’m making it sound like some kind of massive grieving process!), and once I’d got used to not having it, I didn’t miss it at all. Even after the experiment ended, I still spent my evenings knitting and reading. I was surprised – and pleased – to find that I could actually manage just fine without it.

A lot of the 1940’s lifestyle is a frugal one; did you find you saved money as the year went on?

Yes, definitely. The price of my weekly food shop went down drastically as a result of rationing. At one point, I was only spending around £10 a week on food (just for myself). The bulk of what I was buying was seasonal vegetables: things like potatoes, carrots, and

cabbage, which tend to be some of the cheapest options anyway. Added to this were a very small amount of bacon, meat, butter, cheese, and so on, and perhaps one tin, if I was lucky, or some dried beans and oats. When I added a few modern-day luxuries into my shopping basket after the experiment ended, they ended up doubling my wartime grocery bill. It’s a valuable lesson to learn from, as we go through the cost of living crisis now. If money gets tight, especially this winter, I’ll be cutting our shopping list back to something more wartime-appropriate. Even if the average cost of basics goes up, we’re still not worlds away from the 1940s experience. In those days, groceries took a far bigger chunk of people’s wages than they do now. In relative terms, our shopping is cheaper, but we’re used to buying far more, and of course, we have a lot of other costs to account for these days, too.

I was really struck by how lonely you felt in parts of the experiment, a big part of the appeal for many people about the Home Front is the camaraderie and that people were all in it together, do you think it would have been easier if you had been doing it at part of a team?

I think it would have made a huge difference if I’d been doing it as part of a group or community. And actually, that was one area of my experiment that was completely

inaccurate. During the war, everyone was in it together (not in a rose-tinted way, but in the literal sense of everyone going through the same things, like rationing, shortages, stress, and so on). Individual people’s experiences obviously varied, but for the average Home Front woman, there would have been a lot more interaction.

One thing I could really tell from wartime diaries (and from talking to people like my grandmother, who remembered) was that rural communities were fairly sociable places; neighbours were a lot more involved in each other’s lives, there were lots of community groups and events, and also things like the Women’s Institute and WRVS. Nowadays, because we can travel out of our towns and villages, and many of us are out of the house at work during the week, we don’t have the same level of enmeshment with our close neighbours. So yes, my experiment was very lonely and isolating at times, as I was the only person experiencing my particular frustrations.

With the restrictions of the pandemic over the past few years, I’m curious to know if you felt any similarity to when you did your project and the Home Front?

Almost as soon as the pandemic began here in earnest, I was struck by how much elements of that experience reminded me of the Home Front. Obviously, we had masks (though different ones), but there were other things too: being separated from loved ones, shortages of certain items, and facing the worry and threat of a peril that ordinary people couldn’t do a lot about.

In 2020, when my son’s birthday was coming up, I had to save up my last little bit of remaining flour to make his cake, as I wasn’t sure when I’d be able to get it again. Not having everything immediately on hand, and needing to plan ahead and make substitutions, was a very familiar wartime thing. It was also fascinating to see how people immediately began stockpiling, which was exactly what happened in 1939. Human nature clearly hasn’t changed, even though decades have gone by. I’m not judging, though – I can understand why laying instores seems like a sensible move. In a wider sense, the news was full of it, and most of us were tuning in for regular updates from the Government. The nation was united in facing a common enemy, and it was one of the most surreal experiences. It was also interesting to feel that we were living through an actual moment in history here – obviously, we’re always living through history, but this was(is) something that will be included in the books in years to come.

Do you think it would be harder to conduct the experiment now, nearly 10 years down the line, as technology and our phones play a larger part on our lives?

As I’ve mentioned, I missed television initially, but I don’t remember missing the internet much during my year. Even though it was a part of everyday life at the time, now that it’s almost 10 years later, we’re definitely more dependent on it. There are so many elements of ‘life admin’ that rely on it now, before we even begin considering things like social media and streaming. I

think it would be much harder to give it up these days – although I would really love to! How liberating would that be, just for a while?!

What was your favourite part of the experiment and did any parts come as a surprise?

I loved how productive I was during ‘the war’. Because I didn’t have so many modern-day distractions, I naturally got bored at points and so found new things to do with my time. In the drier months I was outside a lot, digging in the garden, foraging for food, walking, and so on.

And in the winter, or the evenings, I was in the kitchen or doing things like knitting, sewing and mending. I was surprised by how much self-worth this gave me. Even now, so many years on, I find it hard to be non-productive for very long. I tend to ‘potter about’ a lot if I’ve got

time to myself.

Once your war was up, did it feel strange when you started back into the real world?

I really struggled to adjust again, actually, and I hadn’t expected that. I thought I’d be cheering and eating junk food at midnight on the last day, but it didn’t feel like that at all. For the first few days, I basically ignored the fact that the experiment had finished, and just carried on anyway. A year is a long time, and I’d got used to it; I felt quite pressured and resentful when people kept telling me that I was all done now, and could start ‘living’ again. I realised that there was a lot I loved about the 1940s, and I didn’t want to give that all up.

I was also really surprised by silly things like how bad modern processed bread tastes. If you haven’t eaten it for a while, you can taste all the preservatives and sugar that’s in it, and it’s a bit disgusting. I think my life now is a compromise between how it was before and during the experiment; it sounds rather earnest, but it did fundamentally change me, and so there are things that have become a part of my everyday life based on that year.

I’m trying to live by a list of Home Front Solutions to see if my life can be a little happier, healthier and greener and I’d love to know what do you think are the top 3 lessons we can learn from 1940’s?

You’ve got a brilliant list of solutions, and they’re all valid. If I had to choose three top lessons from the 1940s, they’d probably be these.

It’s ok not to have what you want all of the time. This sounds really harsh, but I think we’ve all got so used to having whatever we want, whenever we want it, that we’re collectively outraged when we can’t have it (we’re like real-life Veruca Salts, stamping our feet and wanting it now). We’ve got next-day delivery, on-demand viewing, credit cards, buy-now-pay-later, all-year-round fruit… But actually, a little bit of self-denial can be a really positive thing. This encompasses eating seasonally and locally, buying second-hand, waiting for things, and mending what we have rather than buying new. And with this perceived hardship also comes a lot of reward; waiting for things, and then getting them when it’s the right time, can be so much nicer.

Think locally. Globalisation has brought a lot that’s good, but it’s also problematic for a huge raft of reasons. Thinking on a smaller and more local scale can be really beneficial. This might be going into your local library or bookshop instead of buying a paperback on Amazon, or it might be buying eggs from the little neighbourhood stall up the road, rather than the supermarket. It contributes to a far more evenly shared economy, and usually, it’s better for the environment.

Challenge your autopilot. I’m as guilty as anyone of turning on the television at the end of the day, and flicking idly through about five different streaming services. Or of having a spare five minutes, so going straight into Instagram and endlessly scrolling. Don’t get me wrong – I enjoy television, and I enjoy Instagram, and they both have their place in my life, but I think they’re best saved for when you make a conscious and definite decision to use them (e.g. ‘I really fancy watching that film tonight, so I’ll put it on’). My experiment proved how much technology can become a habit, and how much benefit there is to be had from breaking that habit. I recently felt myself falling back into this trap, so now I’m trying to challenge my own autopilot and spend some evenings doing other things, like reading a book, sewing, or listening to the radio and making something. Anything to add a bit of variety and do something slightly more productive.

I reckon you’ve pondered a few times what it would be like to grab a time machine and whiz back to the 1940’s but if that was reversed and someone from the Home Front arrived in today, what do you think would be the one thing they would find the most surprising?

When it comes to food, I think they’d be surprised at the variety of cuisines and ingredients we eat now. Even just in my everyday home cooking, in an average week I can be dipping into elements of Italian, Chinese, Thai, Moroccan, without even thinking about it. Taking them into a supermarket would also be interesting. My grandparents didn’t really eat pasta as it was a bit ‘out there’, so imagine a wartime person faced with oat milk, quinoa, halloumi, fresh lemongrass, Piri Piri crisps…

There’s also a lot technologically that’s very different. I think someone from the 1940s would be completely bemused by our reliance on our phones. They’re always with us and we’re always on them – whenever something happens, you can see a great sea of phones, pointing in one direction. We experience everything through the camera screen.

And keeping my time machine idea in your head, if you did go back what war work do you think you’d most be suited to?

This is a great question! Realistically, I’d probably be best as a Land Army girl, as I’ve grown up in the countryside so I’m reasonably practical when it comes to growing things and milking animals. But I’d love the idea of being in the WAAF – this is largely to do with the uniform (of course!), but it would also have been very exciting to feel you were engaged in “serious” war work.

How did the opportunity come about to write the book?

It all ended up being ridiculously easy, which I know isn’t the typical experience. I had the idea for the experiment and decided that I was going to do it, regardless, but sent a short description of the idea and the process off to a few history publishers, just in case I could wangle a publishing deal too. Amberley came back to me quite quickly, I filled out some proposal forms, and then they were basically saying, ‘yes, go ahead and get started’. I was so grateful that they were willing to take a chance on me in that way.

Do you have any more projects/books in the woodwork?

Yes, but nothing “established” enough to talk about yet! I’ve been working on a novel for what feels like forever, as I never make enough time for it. I now work as a writer, so sometimes when that’s all done for the day, the last thing I feel like is sitting back down at a computer.

I’ve also got an idea for another non-fiction book in the pipeline, but it’s still very early days on that one. I’m planning it out at the moment, which is always an exciting stage.

End

I’d love to know your thoughts on the book and this interview, did it give you a bit more in depth to the book or make you think a little differently about things? Just comment below or come over to my socials to join in the chat.

Side note: If you would like to get your own copy of the book, please use your local bookshop, they can get nearly all in print books to you in a matter of days and are a wealth of knowledge that we don’t want to lose. Alternatively if you do need to buy online, use the Bookshop.org who give a percentage of each sale to an independent book shop of your choice.

This is part of our new Meet the… where I hope to bring you interviews with authors, creators, reenactors and anyone who has a love of the Home Front. You’ll find them under the Here and Now heading or under the Meet the… tag.

Hatty Harley View All →

I am a pink haired, list lover with a silver lining outlook on life and a passion for reviving history.

Loved this interview! Megan’s top three lessons are so timely.

LikeLiked by 1 person

They really good aren’t they 🙂

LikeLike

I enjoyed reading your interview, thank you. I couldn’t imagine following a year’s rationing. I followed Sophie’s (@thymeforhomelife I think) Month long one and remember her saying it was a healthier lifestyle, particularly foodwise. I could quite happily not have a TV, it’s on far more than I like for my husband. I’m reading lots for February & March – library book orders – they always come at once. After that I’ll try to read Megan’s book.

Cathy x

LikeLiked by 1 person

Oh I love Sophie’s blog! And I do remember her month. I think it gives chance for a reset but I agree with you I don’t know if I could do it.

Oh do, her book is lovely ☺️

LikeLike

I loved this interview and it has made me want to re-read the book. I love the idea of incorporating lessons from WW2 homefront into our modern days lives. I love your blog Hattie. ♥️

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you 😊 I’m really glad you enjoy it

LikeLike